If you google “Hunger Games Japan” as I did, you’ll find an endless parade of articles and blogposts directly and indirectly suggesting that Suzanne Collins borrowed from (or less generously, ripped off) Koushun Takami’s novel Battle Royale, often with a list of point-by-point comparisons between the two.

Ultimately, though, that kind of discussion isn’t very productive, leading nowhere but a kind of literary he-said-she-said; and in any case literature and myth are laden with stories of sacrificing youths and maidens to a higher authority. It’s more interesting that each clearly struck a chord in their native countries when they appeared, each becoming a sensation that was quickly adapted to film.

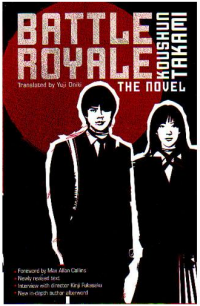

Battle Royale, published in Japan nearly a decade before The Hunger Games first appeared, hasn’t really caught on in the United States, though it’s known just enough to provoke those comparisons and accusations. The ultra-violent film has a certain cult cachet among aficionados of Asian cinema and genre movies (particularly of the Quentin Tarantino sort), but neither book nor film has gained much cultural traction in America otherwise, not even enough to successfully spawn an American, English-language remake. (It’s probably safe to assume that the Hunger Games film effectively buries any possible Battle Royale American version, at least for the foreseeable future.) One might find it reasonable to wonder why one post-apocalyptic story about teenagers forced to kill teenagers has managed to gain a large mainstream American audience, while the other remains relatively obscure.

The language barrier, of course, is the obvious problem; most people, regardless of their own mother tongue and that of the film they’re watching, still don’t like subtitles. And it has to be said that the English translation of the novel Battle Royale isn’t great prose. Not being a Japanese speaker, I can’t speak to the quality of the writing in the original; however, for a long time, the only English version was a poorly-edited translation laden with typographical errors that was nearly impossible to read without wincing. The 2009 translation is a vast improvement—for one thing, it’s clearly known the loving touch of an attentive editor—but the writing still never quite rises above functional and pedestrian. Collins’ writing might not be the most refined, but it’s certainly engaging; you’re going to be turning pages a lot more quickly there.

Compared to the first-person narrative of The Hunger Games, which keeps the reader firmly in Katniss’s back pocket throughout the entire trilogy, Battle Royale operates with a chilly distance from its characters; even though we spend most of our time with the level-headed, likable schoolboy Shuya Nanahara, the narrative voice never seems gets as close to him as Collins does to Katniss. It’s a tone entirely appropriate to both the subject matter and the scale of the cast—with forty students, you can never really get that close to any of them, although Takami does manage to tell you just enough about each one to invest their deaths with meaning. That sort of narrative coldness seems to be a hard sell in the U.S., particularly in stories where young adults are involved.

As many of the other thoughtful posts here at Tor.com have pointed out, The Hunger Games resonates with American readers in the ways it touches on so many of our current anxieties and obsessions: teenage violence, exploitative reality television. As well, the characters’ literal life and death struggles serve as a metaphor for the intensity of adolescent experience with its shifting loyalties and seemingly arbitrary adult-defined rules; the physical violence of the Games is felt as strongly as the psychological violence a teen bully inflicts on his victim.

Though the cast of Battle Royale is a group of 15-year-olds, Takami’s target isn’t particularly youth culture or even popular culture, although the film does play up those elements, as in the unruly class scenes at the beginning and the game-show style video that explains the game to the students. The novel is a savage satire and an indictment of passive societal acceptance of authority. Unlike the Hunger Games, only the winner of the student battle makes it onto the evening news, and the game itself is conducted in secrecy. The battle system, to which a randomly selected class is subjected every year, acts as a kind of punitive tool on the subjects of the Republic of Greater East Asia—and in contrast to Panem, where force and starvation are systematically used to suppress the poorer districts, the Republic seems willing to offer just enough petty freedoms to their subjects to guarantee their acquiescence to the annual slaughter of children. The reasoning for why this works is arguably intimately tied into the context of Japanese culture, as the character Shogo Kawada points out:

I think this system is tailor-made to fit the people of this country. In other words, their subservience to superiors. Blind submission. Dependence on others and group mentality. Conservatism and passive acceptance. Once they’re taught something’s supposedly a noble cause by serving the public good, they can reassure themselves they’ve done something good, even if it means snitching. It’s pathetic. There’s no room for pride, and you can forget about being rational. They can’t think for themselves. Anything that’s too complicated sends their heads reeling. Makes me want to puke.

Of course, a reading not just of Collins, but of the dystopias of Huxley, Orwell, and Atwood that passive acceptance of authority isn’t unique to Japan. Still, Kawada’s rant, positioned halfway through the book, seems to be specifically directed inward, toward his native country, regardless of what name it might be going by.

These differences aside, both Battle Royale and The Hunger Games are driven by disgust at systems that are willing to throw their children to the wolves—whether it’s to maintain order, provide national entertainment, gain a touch of economic security, or some dreadful combination of the above. As such, it’s not really helpful to argue about whether Collins was even slightly influenced by Takami or by the film—and she says she wasn’t. It’s more interesting to read them both for their respective central themes, and to note that in both cases, the literal sacrifice of the future leaves the characters—and by extension society at large—with deep psychic wounds that will never really heal.

Karin Kross lives and writes in Austin, TX. She can be found elsewhere on Tumblr and Twitter.